Why do urban affluent class, who are surrounded by extreme form of materialism, think – surviving in nature, in raw-dense forest, the territory ruled by the mighty Bengal Tigers – would add fame and glory in their already “successful material lifestyle”?

Is it true that despite of our all-out effort in integrating economics and environment, as last desperate attempt to save this planet, deep inside of our heart we all believe it is not the “anthropocentric ecology” but the “deep ecology” which reinforces the core of the foundation of our very survival-success in this planet?

The urban affluence is sustained by market economy and to respond to the need of market economy we have relentlessly commodified nature. To achieve the process of that commodification we integrated ecology and economy and named that cocktail conservation approach as “sustainable development”.

However, we do not have much trust on the “sustenance” of “sustainable development”. Therefore, as a community, we support “sustainable development” in public; and as an individual, secretively we look for every opportunity to live life based on philosophy of “deep ecology”.

When we successfully survive the “deep ecology” based life style for a short time period, we go back again to live the life of “sustainable development” to join the larger community as response to the need of market economy. Once we go back, we sing the glorious songs of our survival in “deep ecology” based life style and proclaim our proximity to nature. We do so just to surrender ourselves again to the usual materialistic life style, which we are comfortable in living and brainwashed to live.

For a sizeable population of urban nature lovers, this is the life cycle pattern. Living a self-contradictory life and making all effort for self-consolation to shield themselves from the ruthless reality of materialistic life style.

The 72 hours survival story of eight men and women of urban affluent class, in the buffer zone of Bandhabgarh tiger reserve, at the onset of monsoon of the year 2021, was all about this conflict between “deep ecology” and “sustainable development”.

These eight men and women, known as “survivor in making” were put together inside the dense forest of Bandhbhgarh National Park and tiger reserve, by an India based organization known as Jungle Survival Academy (JSA). The organization, with the help of local traditional forest dwellers, and ex-Indian Army service men designed a 72 hours survival course to enable non-forest dwellers to fight fears of forest, as well as live a dream in the wilderness of the Bandhavgarh Jungles in Madhya Pradesh. The idea was to let the urban folks to experience the wild, to explore the unexplored and to challenge their inner self to survive in an unknown terrain with very few available resources. As proclaimed by the Jungle Survival Academy, they bring to us (non-forest dwellers), one of its kind survival courses to test our spirits and to make our adrenals rush to fight and survive in the wild.

Most interesting part was that, they document that entire survival challenge, as the “survivors in making” were chased by the camera crew during the entire course.

Before I start telling this survival story, let us know about the eight individuals who were the selected one for this challenge.

Soma Ghosh from Lucknow. A radio jockey and presenter who works for a State Government influenced FM channel of Lucknow city. A lady in her late thirty or early forty, separated from husband and stays with parents, who was looking for a meaningful and exciting life and found participating in adventure sports is a great way of adding more colors in life. In her own verbatim, she participated in bungee jumping, river rafting etc. and participating in a jungle survival challenge would add “another feather in cap”. Soma was someone who came to forest with contrasting bright clothing, a bagful of cosmetics and other make up accessories. In several instant during our jungle stay, we found her applying those in the middle of forest or under a tree top.

Akash Shrotriya from Bhopal. A guy in his early thirty and I never understood why he was there and what was his expectation. Apparently he runs his own NGO which is involved in community welfare and wildlife awareness programme. Throughout the stay in jungle, he kept giving contradictory statement on and off camera. However, he was one of the fittest ‘survivors in making” in the team but always critical about JSA and its instructors (off camera of course).

Ojas Mehta from Surat. A business man by profession and a body-builder cum model cum Netflix TV series actor by hobby. Like most of the body builders he looks strong and capable of taking any challenges, but always particular about dietary preferences. In this entire course, he kept missing his high protein diet and regular hydration plan and he was quite vocal about that. Ojas is also an ex-cricket player who represented Gujarat state in Ranjy trophy. He is highly connected with top-notch Indian national cricketers and Bollywood movie stars. His primary objective was to create plenty of video footages of his survival activities in wilderness. He surprised all of us, when he told that he was 49 years old, whereas he was actually looked as in his early 30.

Neha from Delhi. A 29 years old marketing professional with a multinational company and a Yoga instructor and trekker by hobby. She is fit, strong and up to any challenges but again like most of the fitness freak, very particular about diet. She loves talking about herself and kept mentioning during course, that how much she was missing her three meals a day. Like Soma, she also came with a mind-set of participating in another adventure sports, but with right kind of mental and physical preparation.

Mahim from Noida. A Corporate Trainer by profession, but that’s not his real identity. He was the most royal amongst all “survivors in making” and it was started getting revealed as the challenges becoming tougher. Despite of his honest attempt to remain modest and polite, his uncomfortability due to hardship of living in wilderness became gradually apparent. He is a descendent of the King of Patiala, and his royal lifestyle made him look vulnerable in raw nature. Like Akash, I was not too sure about Mahim’s purpose of being part of this course. Initially I thought it was because of Neha. In first instant both of them appeared to me like a couple, as they were wearing similar clothes and shoes and travelling as well as staying together. In fact, during introduction, Neha told us that they were together. But gradually they went into a denial mode, and we got to know that although Mahim was single but Neha got married six months back.

Rishabh Goyel from Delhi. The youngest in the group. Another businessperson who runs few departmental stores and manages a family run business to feed 18 members of his family. He was the one amongst all the participants who was more candid about his reasons of being there. He had a bad accident sometime back and because of that, he went into depression. Once he recovered from his injury, he started looking for something, which would help in regaining his lost confidence to take challenges. Hence, he landed in the middle of that tiger reserve.

Dr. Prakash Arya from Gandhinagar. A paediatrician by profession and pianist by hobby. The most grounded and down to earth person amongst all the people over there. Probably the most suitable candidate for the challenge with strong survival instinct. Over the period, it was realised that survival in wilderness comes very effortlessly and naturally for him. He was probably there to re-assess his already tried and tested ability to survive in raw nature.

Last but not the least, this confused storyteller who is stuck between “eco-centrism” and ‘anthropocentrism”. The man who makes his living by practicing “sustainable development” but wants to adopt the principles of “deep ecology” in his life. I wanted to participate in this course to get an opportunity to stay as close as possible to the “shadow of the Bengal Tiger”. Not that I did not explore tiger territory before, but as a hobbyist wildlife photographer, I was always privileged to avail the support services on demand, which made my survival as comfortable as it could be in any nature holidays. Eco-tourisms are designed in such a way that eco-tourists never get a scope to complain about the facilities provided to them.

From that point of view this 72 hours survival course was quite indifferent about “anthropocentric” requirements and behaviours. Therefore, I thought it would also be interesting to observe struggle and behaviour of other participants in raw nature, who came from different spheres of life built upon hard-core materialism.

In the morning of 26th June 2021, operational manager of JSA, Mukul picked me up from a rural bus stand of Bagdara village, located around 10 km away from the base camp from where our survival journey would begin. While driving me there, a three times jungle survivor and Himalayan trekker by himself, Mukul told me that due to prolonged COVID19 pandemic induced lockdown, the people movement has been reduced significantly, in the villages and on the roads at the fringe area of buffer zone of the tiger reserve. That has increased the free movement of other animals including tigers. Now tiger sighting near any waterbodies at the edge of the forest or in the corridor between core and buffer zone of forest is more frequent. Along with excitement, this piece of information also brings necessary caution for the “survivors in making” as possibility of close encounter with tigers, in that patch of forest, became higher than pre-pandemic era.

Therefore, at the beginning of our course, our instructors – ex-service personnel Colonel Iqbal Mehta and ex special force commander Shambhu aka Ustad ji, spent some time to told us about animals’ tracks and signs and ways to escape any animal attacks.

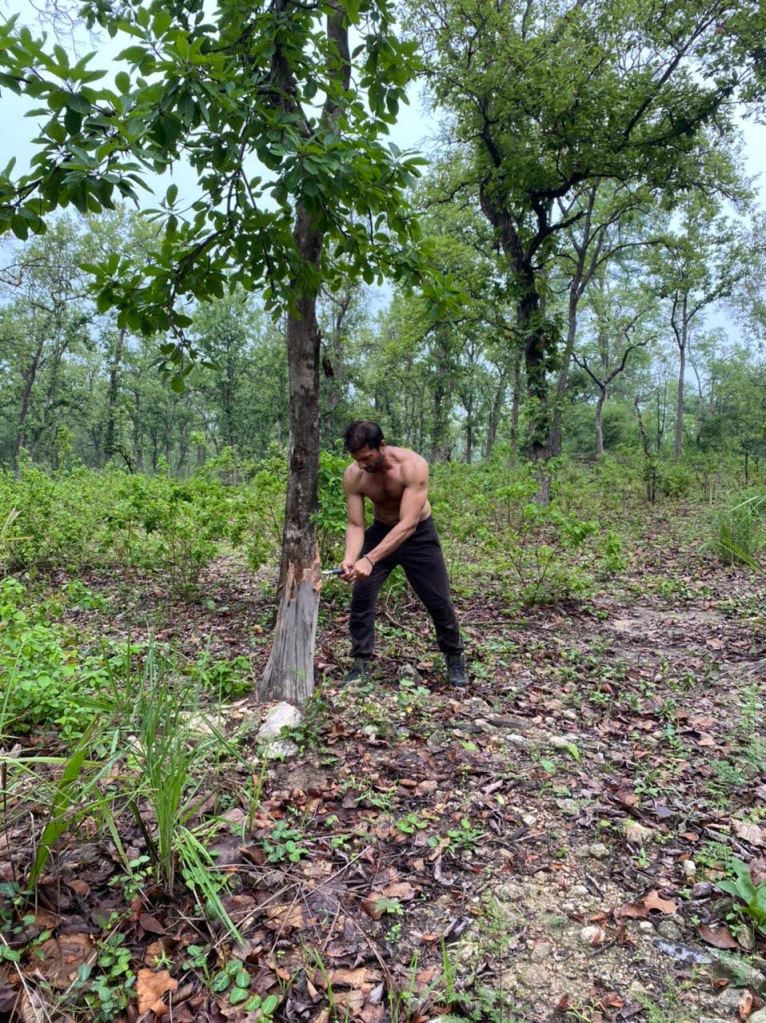

When we started from basecamp, we all were provided with some basic survival tools like knife, axe, head-torch and a whistle. After entering into forest, our first task was preparing spear from bamboo tree with the help of those knife and axe. Both Iqbal and Ustad ji explained and demonstrated how to make and use improvised weapon from raw green hard bamboo. Dislodging a bamboo shoot from the thick stump of bamboo tree needed lot of strength and energy. Although it was monsoon season, but rain was delayed. Therefore, scorching heat was sucking energy and started dehydrating us quickly. I could see, Soma and Mahim started giving up quickly and were looking for aid from others to complete the task.

Besides two instructors, we also had a local septuagenarian forest dweller with us, known as Harshad Dada. With his and Ustad ji’s help all of us could make a spear for each of us which would not just protect us from animal attack but also help during our hiking as well as removing thorny branches of small tree which were coming on our way.

The hiking started and the dehydration due to excessive sweating. We filled our water bottle before we pushed off from base camp, but I could see the water level in my 1 litre bottle was alarmingly going down. When I asked for any nearby water sources, just to raise my panic level, Ustad ji replied, “due to less rainfall, all waterbodies in this forest patch are dry. Therefore we have to wait till we reach our next camping point, where probably we will reach just before dusk.”

From my marathon running experience, I know that my sweat rate is very high and have bad tendency of getting cramp due to excessive dehydration. This thought made me even more worried and I decided to walk as slowly as possible but at the same time keeping a minimum distance with last person of the group. Another way of avoiding any possible predator attack is walking in a group.

Eight of us with three of our nature survival teachers, were not just doing plain hiking. Rather we were doing the most important aspect of surviving in forest, based on naturally available resources. We were foraging, under the guidance of local forest dwelling tribal man, Dada.

Dada was helping us in identifying leaves, tubers, and fungi, which are edible. We were gathering them and collecting in a bag as our lunch and dinner for the day. Tubers of plants locally known as satawari and moori; leaves of a shrub locally known as moker and a circular fungus locally known as koru were the main components of our collection for the day.

Around 2 pm, we stopped at a place to start cooking. We were given ration of rice and black gram (locally known as Urad dal). We carefully used water to wash some portion of that rice and lentil and mixed. We also added leaves of moker into that. Tubers of satawari and moori we chewed and sucked the juice while hiking to keep our lips and tongue moist to cope with thirst. Koru we kept for evening supper.

Lighting fire was the toughest task on that point of time by creating friction between dry tree branches. Even ex special force commander Ustad ji, was almost at the verge of giving up. Although the rain was irregular in early monsoon but enough to make all branches and leaves wet and moist. Thus, lighting of fire appeared as a never-ending process. Once, the fire was lit with lot of efforts, we started boiling all those edible stuff together. However, 30-45 minutes of boiling was not enough and resulted in half cooked rice. Actually, we did not add enough water in rice. We could not do it to save water for drinking as we still have two-three hours to survive our thirst before we find a waterbody.

We all were hungry, so we started eating and appreciating whatever we managed to cook. Only Mahim and Ojas were visibly upset with the outcome. But they also ate quietly.

The last few hours of the day were all about surviving thirst. All of ours bottles were empty by then and we were not even closer to any waterbody. We all were literally dragging ourselves with all body weight leaned on our bamboo stick. Walking through dense forest was nothing new for me. I did that before in the forest of Periyar and Sumatra. But the rainforests provide good canopy cover. On the other hand, the forest of Central India is dry and moist deciduous in nature. There are tall trees but canopy is not big enough to protect from sunlight. Our energy was draining rapidly. Less food and water was making our movement slower.

When we were desperate for water, we reached at a place where forest floor was covered with dry leaves. Ustad ji, picked up one leaf, smelled and poured something from it into his mouth. It was rainwater accumulated in dry leaves. He told us, “If you are desperate to quench your thirst then this is the only option available for you. Walk slowly and come closer so that you don’t step on the leaves containing rain water.”

We all gradually gathered and drank that water. Mahim and Akash were refrained from drinking that water. Later Mahim told us that he could not imagine drinking water like that. Therefore, he thought it was all right to stay thirsty and dehydrated.

Iqbal said, “Smell the water first before you gulp it”. Any foul smell from accumulated water in ditches, or leaves indicates that the water is not potable. There is no other way of measuring potability of water in wilderness.

It became dark by 7 pm, and we reached at camping area, where we had to pitch tent. Ojas and Mahim were expecting somebody to wait with tea and snacks at camping area. When the expectation was expressed, we could only get sarcastic laughter from our camera crew.

Once we were done with tent pitching, Soma put on her evening make up, did her hair and slipped into her evening dress. Rest of us dispersed into forest for collection of dry woods to lit bonfire. Another difficult one hour to lit fire and cooking and another dismal outcome as far as cooking quality was concerned.

Ojas was more content this time and accepted the outcome as a natural process in wilderness. Mahim became grumpier and criticised the idea of putting koru (fungi) in food. It was not tasty at all and a bit rubbery.

Whole night was breeze less, and was difficult to slip within tent. Fortunately, we all got our individual tent therefore; it was possible for me to strip down to nothing as an effort to escape from sweating like a pig. Early morning there was a bit of shower but that just worsen the situation.

I got out of my tent at 6 o’clock in morning; the surrounding grassland was still wet and moist. We survived in this tiger terrain for 24 hours and we had 48 hours more to go.

Morning 8 o’clock again we started our hiking through forest. The day we spent in learning unarmed combat and rope making from the leaves of moori. We needed lot of rope for carrying thick woods for creating bonfire and most importantly for making shelters.

Foraging continued besides all these activities. Besides our regular moori, satawari and moker, we added another kind of fungi known as “deema ki piri” or fungus grown on termite tower. The white globulous head at the top of white slender body were popping out from termite towers. All of us happily collected those with a hope of eating a better meal than previous two occasions.

Rope making and foraging took more time than previous day. Meanwhile during our movement, Dada sensed movement of some animal. That made us to sit quietly at a plain grassland and do a detour until he found it safer to move. When we were crossing a ditch full of sand, both Dada and Iqbal drew our attention towards fresh pugmark of a female adult tiger. The tigress clearly walked along the ditch and according to Iqbal that happened probably in the morning, therefore the tigress must be still around that area. Apparently, that area was used frequently by a female and her cub as a corridor between core and buffer zones of Bandhabhgarh tiger reserve.

Iqbal looked at us and said, “Some story to tell others once you survive next 40 hours”.

Experience of tiger encounter in wild, even if it is not the tiger itself but the sign of its presence around you– sign of debuckling on tree trunk, pugmarks on soil – all counts as “some story to tell others”. Everybody – wildlife enthusiast, nature lover, adventure sports person or jungle survivor alike – wants to tell this story to others. This is the story, which makes one stand out from others; this is the story, which makes one brave and cool; this is the story makes one glorious survivor in forest that is ruled by the majestic beast of this subcontinent.

That statement of Iqbal on that very moment in the buffer zone of Bandhabhgarh National Park was enough to establish the glory of Bengal Tiger in subcontinental forest. If one can survive with him in his territory, without causing any harm to each other, then that one has lived few hours of his/her life embracing principles of “deep ecology”.

It was another dusk in forest, and we did not get time to cook our lunch, so it was almost 24 hours we were without any food. But we learnt how to survive thirst by then. Our body and mind was conditioned to live 24 hours of hot summer with 1 litre of water.

As light was diminishing quickly, we had to ramp up our shelter making and cooking arrangement process. We got ourselves divided into two groups to take charge of these two key tasks to face the night in forest, where tiger movement was already confirmed.

In previous day, we were given a cooking vessel, but on next day to make our challenge little more difficult, it was taken away. Therefore, in the absence of our last resort of civilized cooking utensil, the remaining rice, black gram, leaves of moori and deema ki piri were all mixed, washed, and wrapped in leaves. The whole bundle was placed over dry branches inside a rectangular whole dug out in ground with the help of axe and knife. With similar painfully patient effort, the fire was lit and baking of that mixed edible stuff started with the aid of dry wood charcoal. As usual, we were running short of water supply. As we had whole night to survive on a treetop, where the makeshift night shelter or machan was made with the help of bamboo stick and rope made out of leaves of moori plant, we dared not to spend too much of water in cooking.

In the darkness, it would not be a wise idea to venture out for drinking water, especially when predator movement was sensed around us.

The end result was the third consecutive half cooked or barely cooked meal to eat.

Rishabh, Ojas and Mahim decided not to eat anything. Soma, Doctor, Neha and Akash ate as per their best capacity. I hogged that food to fill my stomach, as I wanted a good night sleep.

Mahim was in empty stomach for almost 36 hours by then, on top of that there were spiders near our cooking area. He said that he hates spiders as they spoiled his balcony garden plants. In addition, he also has Arachnophobia. All these literally made him disgruntled.

In the night at the machan, once our camera crew and instructors left us in wilderness to survive rest of the night, the possibility of a coup started brewing under the leadership of Prince of Patiala. Mahim’s royal legacy just refused to accept such ill treatment caused by “uncivilized food” and “unhygienic living condition”. Neha and Ojas supported him softly as both of them were genuinely missing their rigid diet regime. As a result packets of glucose biscuits arrived at machan to serve his majesty and his hoi polloi.

Once again the pseudo affection for nature by urban affluent class was exposed; once again urban folk’s inability to cope with challenges thrown by wilderness was visible; once again the lack of faith of urban lifestyle towards complete dependency on nature was revealed; once again human’s preference to live as per their own convenient lifestyle over the way of life offered by nature was proven; and last but not the least once again “sustainability development” won against “deep ecology”.

Next day morning, with my surprise Mahim said, actually, he was not hungry but he just wanted to make a point that he deserved food palpable for “civilized” people. The human life forms will always remain entangled in this web of complexity of so-called civilization and keep all other non-human life forms at bay. Hence, defeats the purpose of all human defined conservation concepts- like cohabitation, eco-resilience, eco-restoration and many more.

Everybody’s ability to survive in forest like other non-human life forms were significantly challenged. Nevertheless, we all survived 48 long hours in the wilderness of a tiger reserve of Central India.

Next 24 hours really broke us completely both mentally and physically. The climate was even more hostile due to increased temperature. Few rounds of shower during daytime increased the humidity further to make our life more miserable. In three continuous day, we were in same clothes and undergarments. Everything was soaking wet by our own sweat, which was attracting lot of insects to sit on the open parts of our body, thus increasing itching all over body parts.

We had to manage with lesser supply of water, and again it was another day we were without food. Whole day we were busy in learning how to tie different knots, which may come handy during climbing, material lifting and rescuing; we learnt slithering with the help of rope from 30 feets tall tree top; we learnt how to collect rainwater and filter that with charcoal; and how to make improvised traps to capture animals. Ustad ji was a real artist of all these techniques and taught us with lot of patience. Whole day we were mesmerized with Ustad ji’s military art and Dada’s local knowledge. All these activities did not give us enough time to lit fire and cook food; however, we did not forget to forage for night.

Ojas and I were bit happier than others as we collected enough number of local forest fruits called bael. Aegle marmelos, commonly known as bael, also Bengal quince, golden apple, Japanese bitter orange, stone apple or wood apple, is a species of tree native to the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia. It is present in India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Thailand, and Malaysia as a naturalized species. This was the only edible fruits lying on forest floor in abundance.

I remembered during my childhood my father used to run after me with his concoction made out of this horribly tasted fruits in order to cure my constipation. That time, even in my remotest dream, I could not imagine that one day I would eat this fruit as if it was a panacea from haven.

By the night lot of people thought it was enough of survival and their body was no longer able to take any further toll. Soma, Neha and Mahim decided to leave. Ojas and Akash were in dilemma. Although Akash was visibly tired but he was claiming repeatedly, that he had lived tougher life than this and had seen worse. However, Ojas was quite honest in confessing that he had not gone through such hardship ever in his life. He comes from a background where he does not even need to carry his gym kitbag and protein shake on his own. But here in this forest he was going through all these with a smile on face. Despite of his celebrity status he was quite a down to earth person.

Eventually both of them decided to stay back in machan for the last night of our survival course.

The usual cooking process started for the night, Ojas lost his patience and decided to stay rather hungry. But Ustad ji told us boldly, “You have to cook for me, I don’t care whether you stay hungry or not!”

The message was clear to everybody so we cooked food in similer way as previous night and with all our surprise, we cooked adequately boiled and more palpable food. It was just rice and moori leaves, but the delicious ever meal we cooked durig our survival course.

The next day morning Rishabh, Dr. Prakash Arya, Ojas, Akash and I came out of the forest after completing 72 hours of jungle survival in the tiger territory of a Central Indian landscape.

We all enterd in this forest with different objectives, but we all had one common ground. We all believed that we human are incomplete without any connection with non-human life forms, does not matter how much we underestimate and disregard them. We all also confesed that ability to stay in nature like any other living species of her, doesn’t make us any deregetory species, rather magnify our fame and glory as human being.

All eight of us would be indulged again in our regular life to respond to the need of metarialism. Nevertheless, my journey to embrace “deep ecology” began.

Nice one Arnab.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s quite interesting… Adventure

LikeLiked by 1 person

so very well understood and articulated Arnab. The pseudo centricity of the elite human race

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Arnab glad you picked the essence of the concept quite accurately. Well elucidated.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Col Mehta for all your teaching and guidance, it was a life changing programme for me

LikeLike

Colonel Iqbal ! I couldn’t thank u personally

But here from the core of my heart , i m thanking u for making me more strong & enhancing my skills .

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad to be a part of it . You have poured our feelings , thoughts, emotions too in it . Good Job Arnab 👏🏻🤩

LikeLiked by 1 person