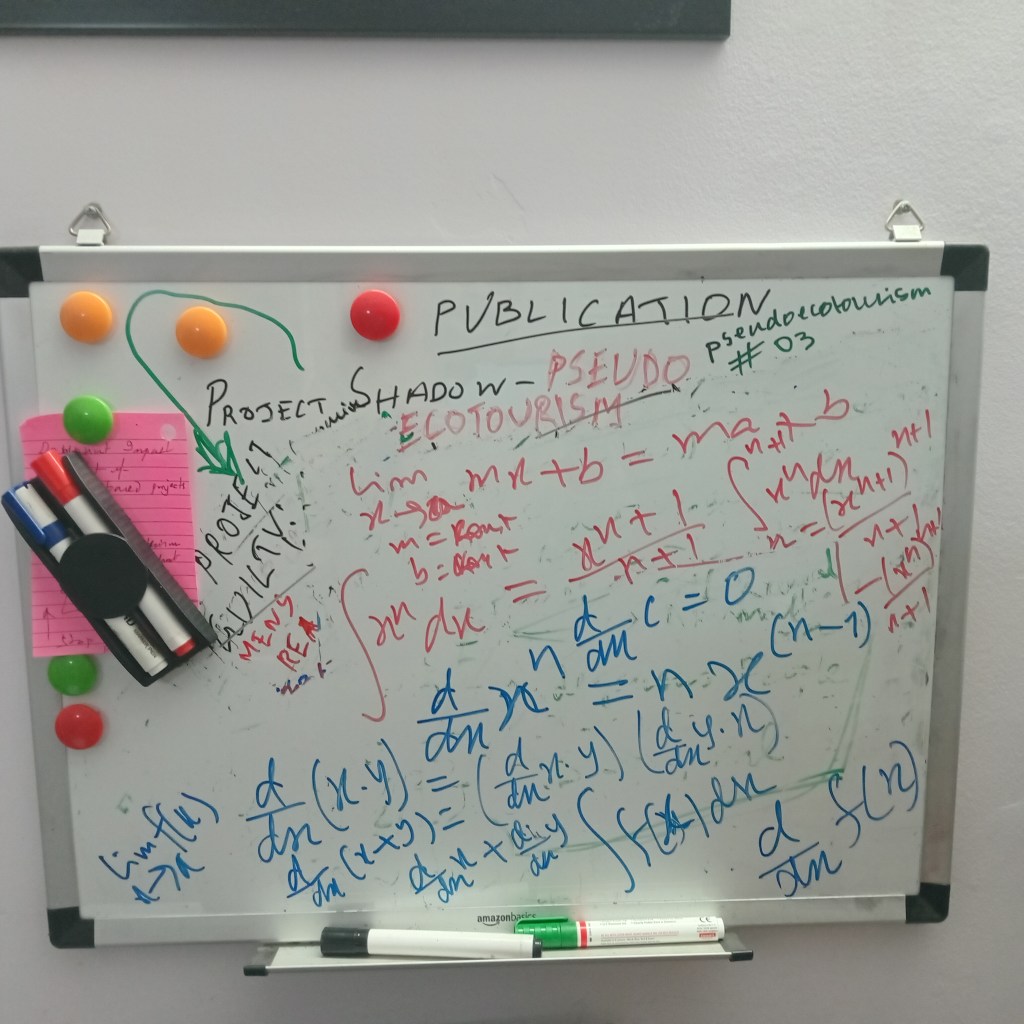

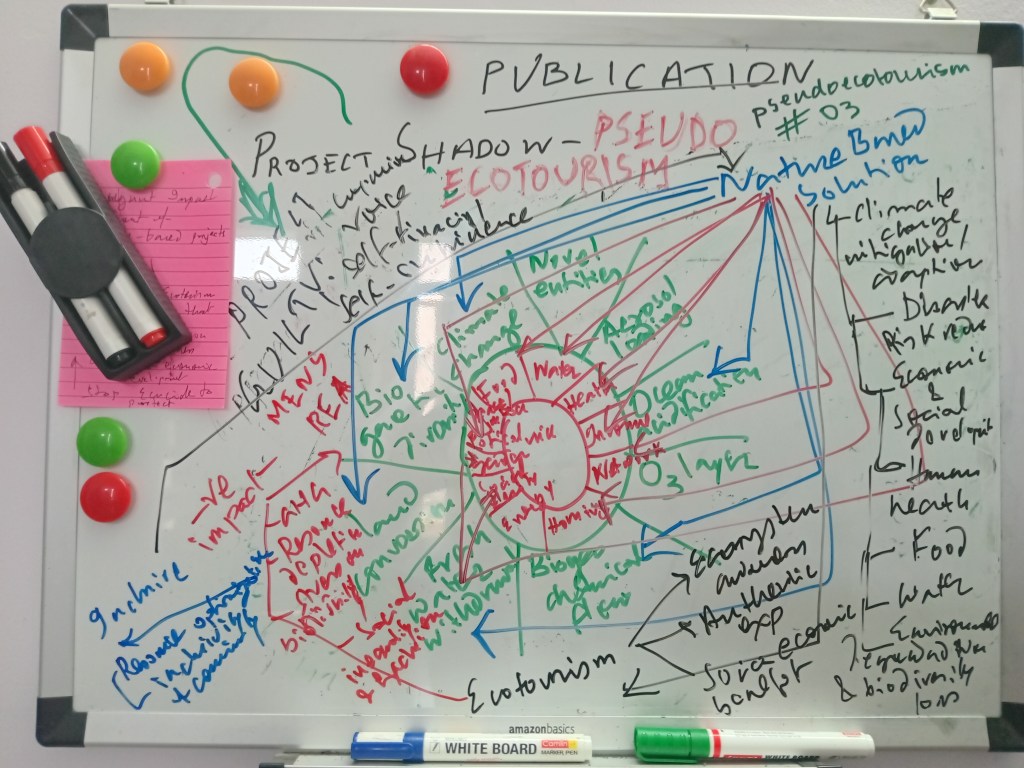

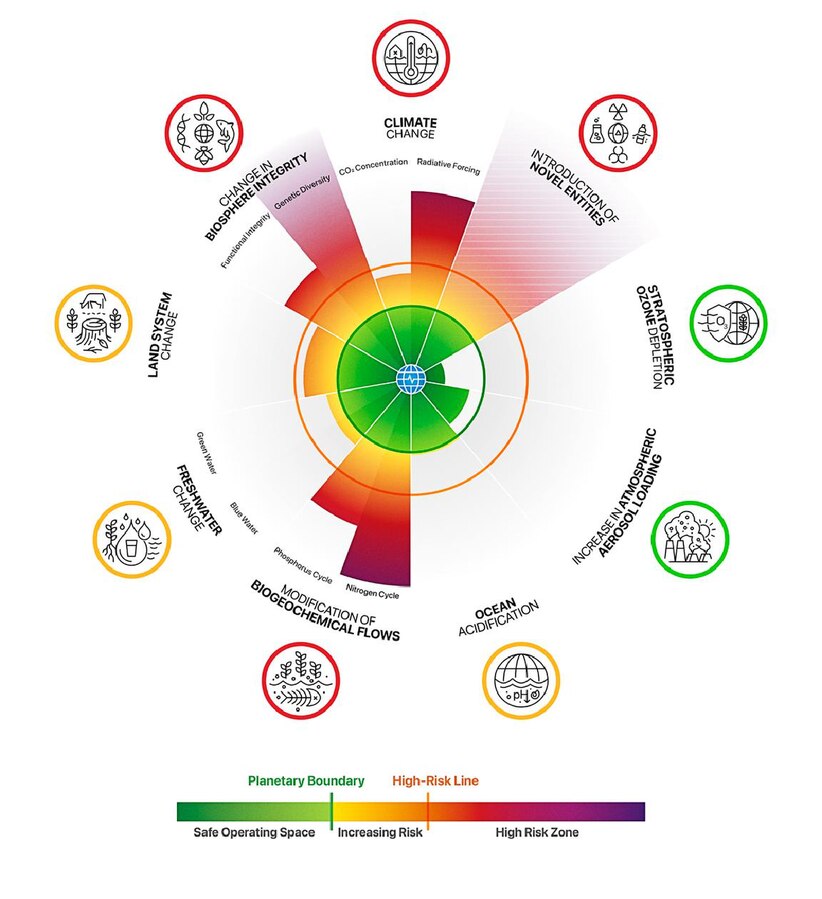

In 2009, several scientists from Stolk home Resilience Centre, under the leadership of Dr. Johan Rockstrom introduced the concept of Planetary Boundary, which defines unbreachable nine, quantified limit for the planet, for safe and sustainable living. (Ref: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Planetary_boundaries)

In 2012, the Oxford University economist Kate Raworth, built upon the concept of planetary boundary and introduced the concept of Doughnut Economics, by incorporating twelve social blocks (Ref: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doughnut_(economic_model)).

Both the model not just challenged the concept of traditional development and economics but also challenged the concept of exponential growth. And, in another way they challenged the traditional definition of sustainable development, which more often than not sounds like an oxymoron. The concept of United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) allowed trading off between various goals.

(Refer: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sustainable_Development_Goals)

To ensure zero hunger (Goal 2), we may need to prioritize decent work and economic growth (Goal 8), and to ensure that we may need to focus on industry, innovation, technology and infrastructure (Goal 9), and that may climate action (Goal 13), life below water (Goal 14) and life on land (Goal 15) to back-burner.

This is how the vicious cycle between conservation and hunger starts.

Based on a research paper, Socioeconomic impacts of small conserved sites on rural communities in Madagascar, by D. Rodríguez-Rodríguez et al, published in Environmental Development, “Madagascar is one of the most important global biodiversity hotspots, where high endemicity rates spatially coincide with rapid loss of natural habitats (Mittermeier et al., 2011; Ralimanana et al., 2022). Madagascar is also one of the least developed countries of the world, ranking 173 of 191 in the Human Development Index (UNDP, 2022). Poverty and lack of access to basic services is widespread in rural areas, where populations heavily depend on the collection of natural resources for their subsistence (World Bank,

2021). Whereas Madagascar’s biodiversity is mostly hosted by the variety of forest ecosystems present on the island (Goodman and Benstead, 2005), these ecosystems have been rapidly declining due to human activities in recent decades to cover just 15 % of the country’s terrestrial area in 2014 (Vieilledent et al., 2018). The major pressures that forests face are the expansion of cattle grazing (Waeber et al., 2015), pioneering slash-and-burn agriculture on the western dry deciduous forests (Vieilledent et al., 2020), shifting cultivation on the eastern moist evergreen forests (Zaehringer et al., 2015), charcoal production, timber collection and mining (Raik, 2007). In addition to habitat loss, biodiversity in Madagascar also faces other important pressures such as poaching and illegal trade of wildlife (Borgerson et al., 2016; Mandimbihasina et al., 2020). Current farming and wildlife exploitation practices help, however, to provide food security (Llopis et al., 2021; Borgerson et al., 2022) in one of the most food insecure countries in the world (EIU, 2022).”

This is the vicious cycle between conservation and basic survival of poor people, which is prominent in most of the developing countries. Now, on which side of it, the ecotourism plays its influencing role, is a good question to ask.

We reached at our destination – Ranomafana national park at around 6:00 pm. And then did a night-walk on the road along the edge of the forest adjacent to the Andriamamovoka waterfalls, until 8:00 pm and then retired for the day when sudden gush of rain had halted us. However, we had already spotted Cryptic chameleon or blue-legged chameleon, Madagascar pimple-nose chameleon and elusive comet moth during our night-walk.

On 13th April, as usual at 7:30 am we headed towards Ranomafana national park and stayed inside the park up to 12:30 pm. The highlights of our sighting were Madagascar scops owl which was roosting on a dim light branch, golden bamboo lemur, ring-tailed vontsira or mongoose, and the most remarkable one from conservation point of view – the greater bamboo lemur (Hapalemur simus), also known as the broad-nosed bamboo lemur and the broad-nosed gentle lemur.

The greater bamboo lemur, is one of the world’s most critically endangered primates, according to the IUCN Red List. Scientists believed that it was extinct, but a remnant population was discovered in 1986 (Wright, Pat (July 2008). “A Proposal from Greater Bamboo Lemur Conservation Project”. SavingSpecies. Retrieved 1 June 2012.). Since then, surveys of south- and central-eastern Madagascar have found about 500 individuals in 11 subpopulations. The home range of the species is likewise drastically reduced. The current range is less than 4 % of its historic distribution. The reason for the endangerment is climate change and human activities which depleted the primary food source (bamboo). This species of lemur is not capable of adapting to the rapidly changing habitat. Human activities and climate change have resulted in the depletion of populations and resulted in a few remaining patches of forest capable of supporting this species. The species is endangered by various anthropogenic activities such as slash and burn farming, mining, bamboo, and other logging, and slingshot hunting (Conniff, Richard (April 2006). “For the Love of Lemurs”. Smithsonian. 37 (1). Smithsonian Institution: 102–109.). As of October 2024, only 36 individuals are in captivity, world-wide (“Cotswold wildlife park successfully breeds endangered Madagascan lemur”. The Guardian. 20 October 2024. Retrieved 22 October 2024.).

The one we saw in Ranomafana during our exploration was an adult female and the only individual survived in that forest. According to Nandih, the local scientists were working on to find few other male individuals as her mating partners in order to conserve the species in that forest.

After lunch break on that day, we explored another side of the forest, the Voiparara Reserve from 3:45 pm to 4:45 pm. The addition to our list of lemurs was Milne-Edwards’s sifaka.

On 14th April, at around 7:00 am we started to proceed from wet zone to dry zone – towards Isalo national park. On the way we stopped by at Anja Forest at around 12:45 pm. The Anja Community Reserve is a woodland area and freshwater lake, situated at the base of a large cliff. Much of the reserve is dominated by fallen rocks and boulders and there are two small caves providing habitat for bats and owls. This reserve has much sheltered habitat in the pocket of forest that has established between the vast boulders. The reserve was created in 2001 with the support on the UNDP to help preserve the local environment and wildlife, and to provide additional employment and income to the local community. The reserve is home to the highest concentration of maki, or ring-tailed lemurs, in all of Madagascar. The people, who have a belief in not eating the maki, used to sell the maki to outsiders. However, after finding that 95% of makis in Madagascar are now gone, the people initiated the formation of a nature reserve, effectively establishing the world’s largest congregation site for makis. Due to its high biological, cultural, and natural importance, scholars have suggested the possibility of its inclusion in the UNESCO World Heritage List. (“Granite cliffs in the Anja Community Reserve near Ambalavao”. GettyImages.com. 6 October 2016. Retrieved 23 December 2017.).

We saw plenty of ring-tailed lemur in Anja. And few more new birds such as olive bee-eater and Madagascar blue pigeon, and few more chameleons – Malagasy giant chameleon or Oustalet’s chameleon and Brookesia or Nosy Hara leaf chameleon. We had left that forest at around 1:30 pm and by that time we reached at our resort in Isalo, it was 8:30 pm. After dinner we did our customary night-walk within the resort campus located within Ranohira village. And we spotted Madagascar nightjar, fruit bat, Madagascar cat snake, and Malagasy hissing cockroach, various other amphibians, lizards and insects. The resort was also home of few radiated tortoise (Astrochelys radiata). Although this species is native to and most abundant in southern Madagascar, it can also be found in the rest of this island. It is a very long-lived species, with recorded lifespans of up to 188 years. These tortoises are classified as Critically Endangered by the IUCN, mainly because of the destruction of their habitat and poaching.

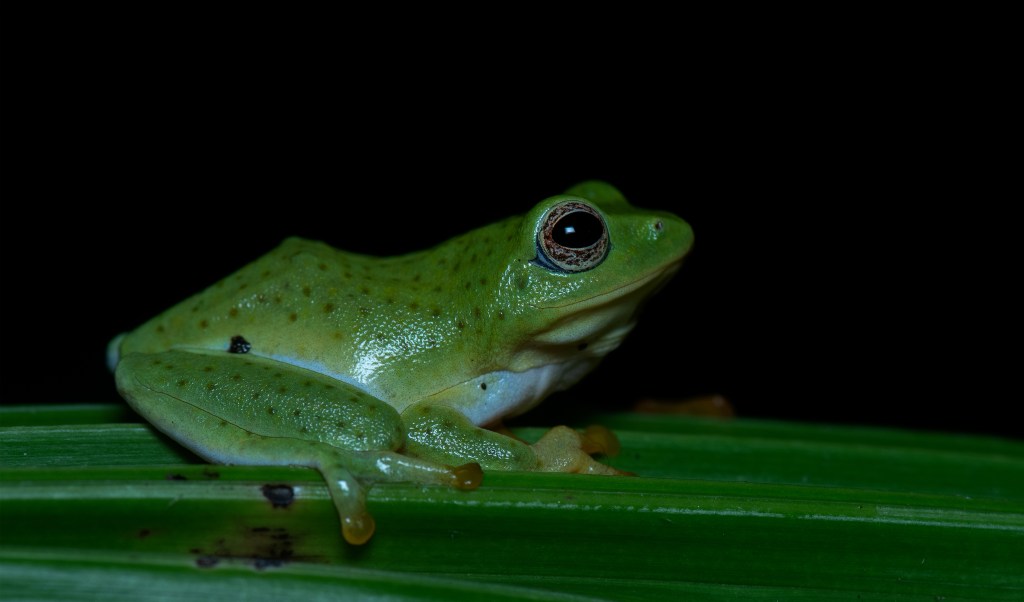

We were about to start the second phase of exploration – the dry zone exploration. According to many of our team members, in the previous zone, i.e., in wet zone, we did not see enough frog species we should have had. In one such conversation during our trip, Achyuthan tried to explain few possible reasons what might have caused that. According to him less monsoon due to climate change, and chytrid fungus were primarily responsible behind disappearance of frog. The chytrid fungus attacks the parts of a frog’s skin that have keratin in them. Since frogs use their skin in respiration, this makes it difficult for the frog to breathe. The fungus also damages the nervous system, affecting the frog’s behavior. Wet or muddy boots and tires, fishing, camping, gardening or frog-survey equipment are suspected to be contributing to the spread of the disease. Achyuthan also said, bushes are thick in rainforest of Madagascar due to absence of any large herbivores. Therefore, there was not much gap between big trees and that could be a reason for not having suitable habitat for frogs.

Researchers Franco Andreone, Mike Bungard and Karen Freeman in their book Threatened frogs of Madagascar, have mentioned, “the frogs of Madagascar suffer from a series of threats, including habitat alteration, deforestation, pollution and collection for the pet-trade.” According to them the biggest threat to Malagasy frogs is loss of habitat, either by deforestation or through the conversion of pristine rain forest into agricultural land. They have also mentioned, amphibians are experiencing a dramatic decline worldwide. Apart from habitat alteration, one of the major threats to frog populations is the spread of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, a fungus that attacks only amphibians, commonly called “Bd” and can result in a disease called chytridiomycosis. The origin of this fungus is not well known, but it has been found in many parts of the world, in both altered and pristine environments. Amphibians as bush-meat cited as another probable reason. Some species of Malagasy frogs are collected by local people for food, particularly large species of the genus Mantidactylus, such as M. guttulatus in central-eastern Madagascar, and Boehmantis microtympanum from the south-east. Another reason mentioned by them was the pet trade. Between 1996 and 2002 over 140 million amphibians were traded worldwide. In 1998 alone over 31000 golden mantellas (Mantella aurantiaca) were exported from Madagascar for the global pet trade. Species most commonly traded are green mantellas (Mantella viridis), harlequin mantella (Mantella cowani), the Baron’s mantella (Mantella baroni) and the expected mantella (Mantella expectata). Golden mantellas (Mantella aurantiaca) and tomato frogs (Dyscophus spp.) are particularly prized by collectors. Because they are active in the daytime and are brightly coloured, they are not only easy to catch but are also popular pets.

Although, there was no specific mention of reduced monsoon due to climate change as reason of disappearance of Malagasy frogs in the research done by Franco Andreone, Mike Bungard and Karen Freeman. However, climate change is projected to lead to an increase in temperatures for the entire island of Madagascar in the 21st century (Tadross, Mark; Randriamarolaza, Luc; Zo Rabefitia, Zo; Ki Yip, Zheng (February 2008). “Climate change in Madagascar; recent past and future”). Climate change is a significant threat to Madagascar’s environment and people. Climate change has raised temperatures, made the dry season longer and has resulted in more intense tropical storms. The country’s unique ecosystems, animal and plant life are being impacted.

With this realization we started our dry zone exploration on 15th April at Isalo National Park. It continued 8:30 am to 12:30 pm. In scorching heat, walking through rocky terrain with no canopy cover not only made our exploration harder but also reminded the real time effect of climate change. Isalo is a sandstone landscape that has been dissected by wind and water erosion into rocky outcrops, plateaus, extensive plains and up to 200 m (660 ft) deep canyons. There are permanent rivers and streams as well as many seasonal watercourses. Elevation varies between 510 and 1,268 m (1,673 and 4,160 ft). Isalo is primarily within the dry deciduous forest ecoregion, an ecoregion in which natural vegetation has been reduced by almost 40% of its original extent.

During our exploration in Isalo, we saw three more new bird species – Madagascar munia, grey headed love birds and Madagascar lark. Among reptiles the interesting observations were Malagasy iguanian lizards, and Jeweled chameleon or Campan’s chameleon or the Madagascar forest chameleon. However, as always, we were fascinated by adding one more lemur species in our list – Verreaux’s sifaka or the white sifaka.

On 16th April, we started our journey to move further towards west-coast of the country. Started at 7:30 am we reached the coastal town Tulear or Toliara at around 8:30 pm. On the way we visited Zombitse National Park between 9:00 am and 12:00 pm. The main landscapes found in the park are forests, woodlands, open grasslands and there are also some limited wetland areas. The opening sightings in the park were a huge hog-nosed snake and then a Standing’s Day gecko. Some mention worthy bird species were lesser varsa parrot, Madagascar blue Vanga, and Madagascar black kite. And of course, Hubbard’s sportive lemur (Zombitse sportive).

The last exploration was in the forest of iconic baobab trees on 17th April in Reniala Reserve of spiny forest between 6:00 am and 9:00 am. Reniala (meaning baobab in Malagasy) Private Reserve is a small 45-ha protected area less than 1km from the Mozambique Channel near the village of Ifaty-Mangily. The bizarre spiny forest (or spiny thicket) is one of the oddest and most unique habitats on the planet. Reniala is a small community-managed reserve of only 45 ha, but is a properly protected portion of spiny forest crowded with species found nowhere else on earth. It hosts more than 2,000 plant species, 95% of which are endemic to this rare habitat, including a whole plant family, the alien-like octopus trees (Didieraceae).

Along the reserve’s botanical trail, we came across some of the most spectacular and oldest baobabs in Madagascar (there was a giant baobab of 12.5 m diameter). It is also a bird sanctuary and early morning exploration generally creates opportunity to sight some of Madagascar’s most sought-after endemic avian species. We could also see Madagascar cuckoo, Namaqua dove, Malagasy Harrier, green capped coua, and the elusive long tailed ground roller.

During our 11 days exploration starting from North-East part to South-West part of the country, in 16 different ecotourism destinations, we spotted and identified around 39 species of birds, 18 species of mammals (including 16 species of lemur), 25 species of reptiles, 12 species of amphibians, and 14 species of insects. But it was just scratching the surface.